TEXT BY MICHAELA MULLIN | VIEW IMAGES

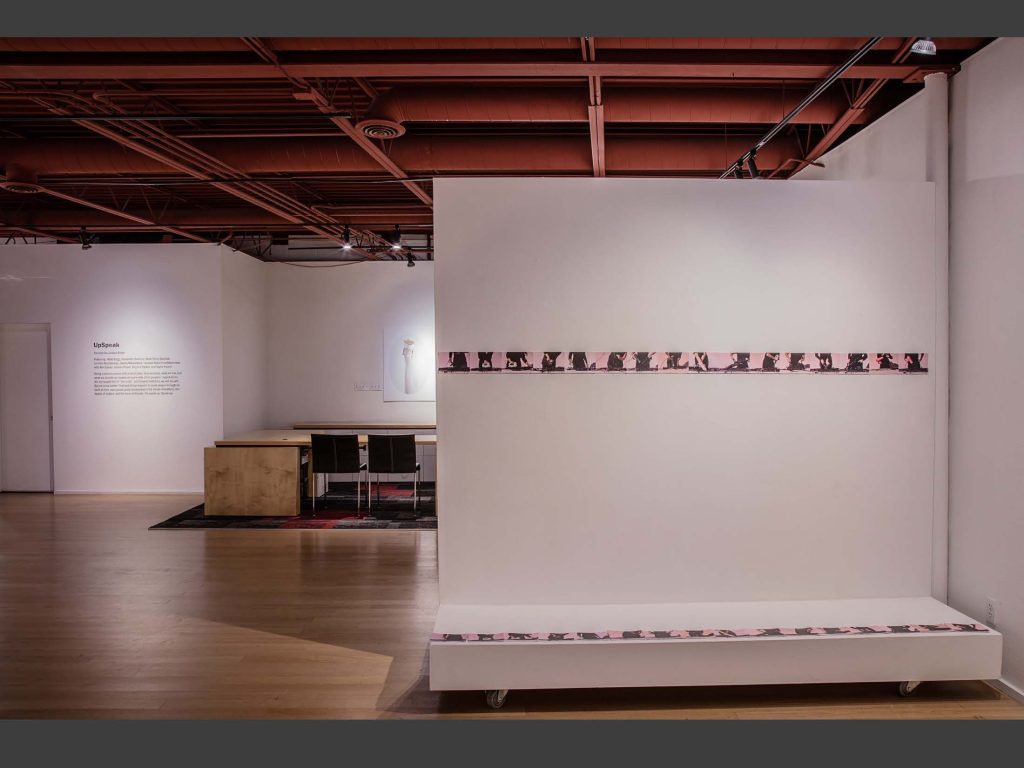

UpSpeak, curated by Larassa Kabel, holds so much power in its images, objects, and performances, both individually and collectively, that the gallery feels supercharged—just as individual women, and women together, have and gain strength. The works Kabel chose for inclusion in this exhibit are dynamic and discursive, and prove to create a unique lens through which to see.

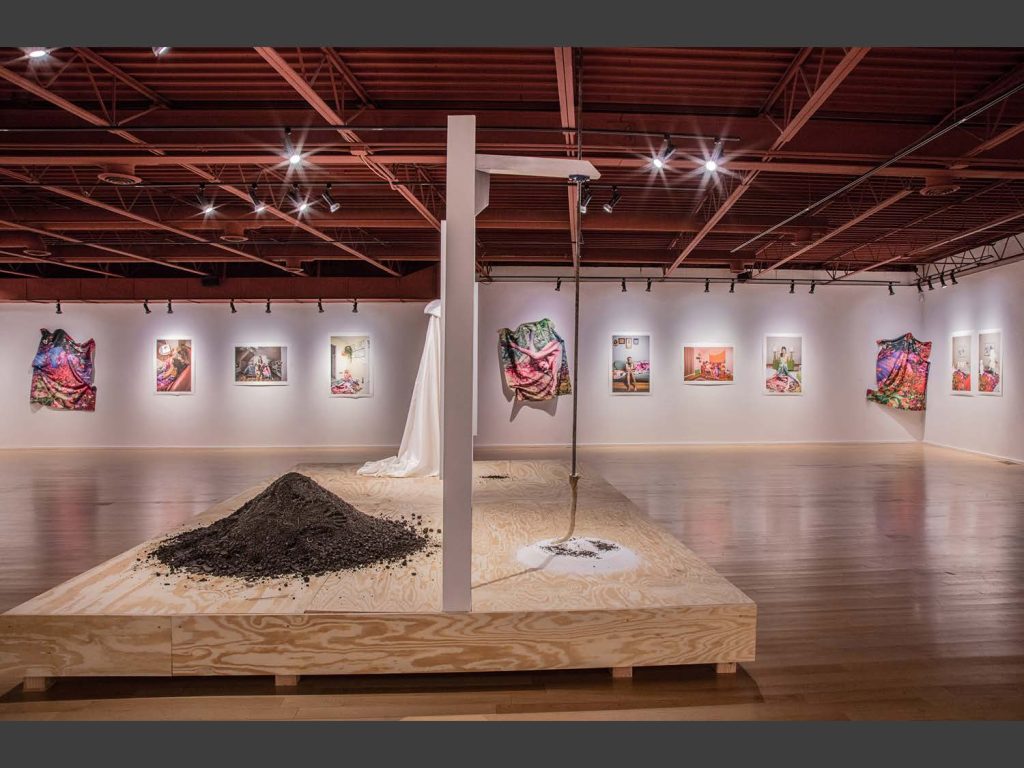

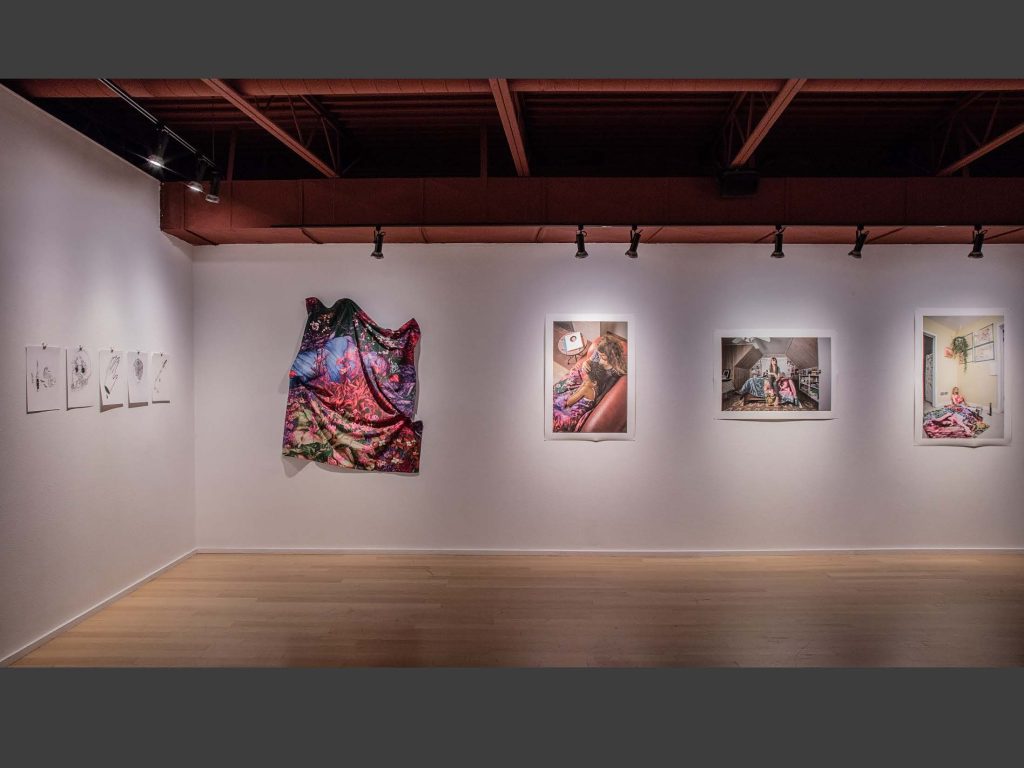

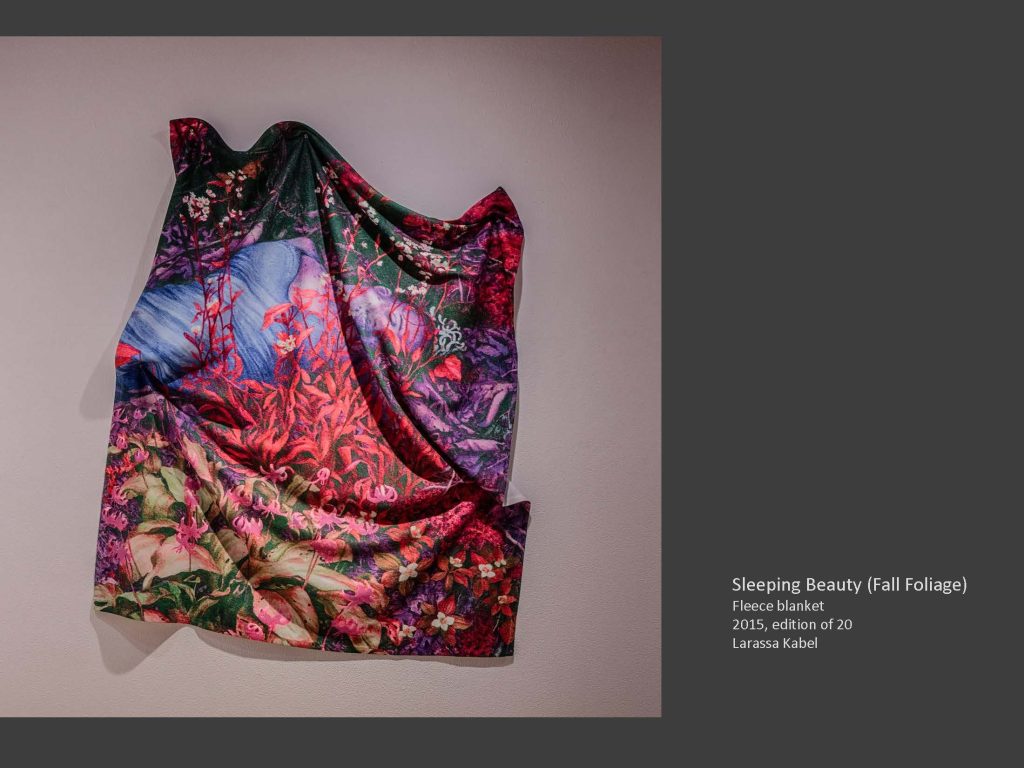

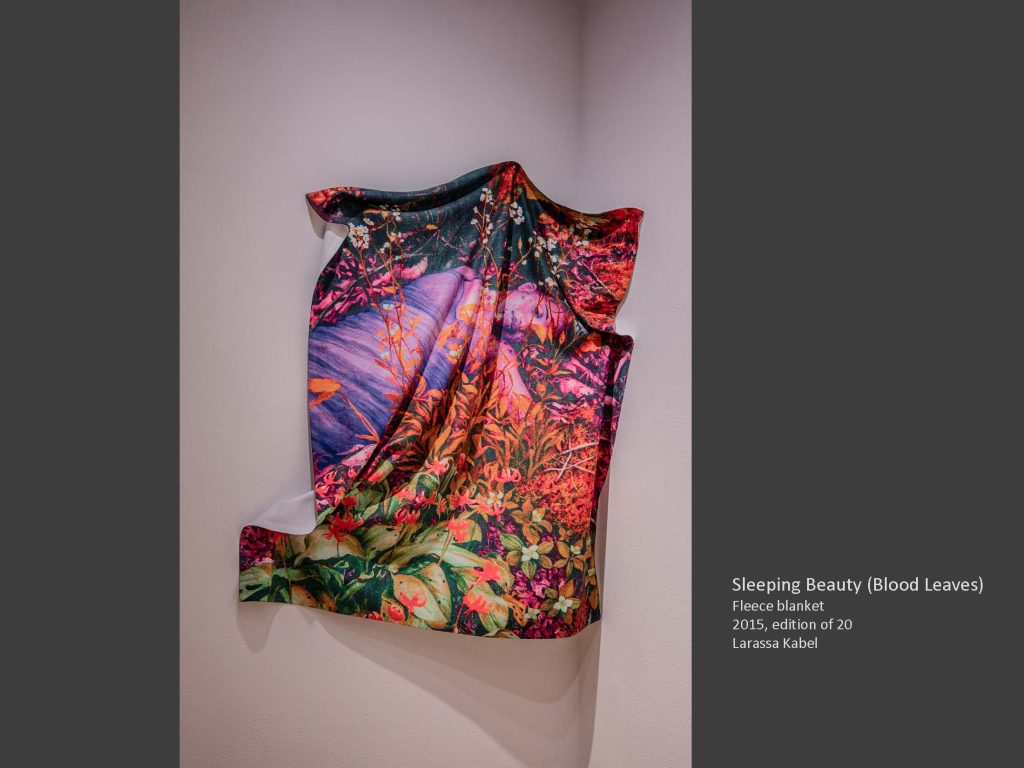

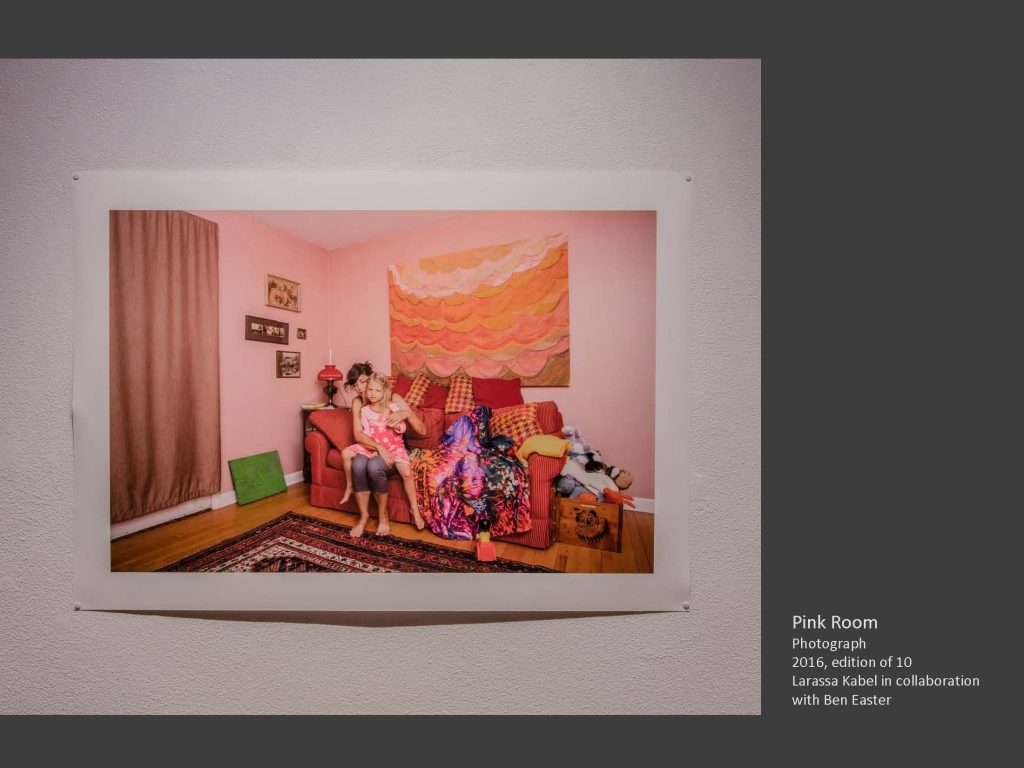

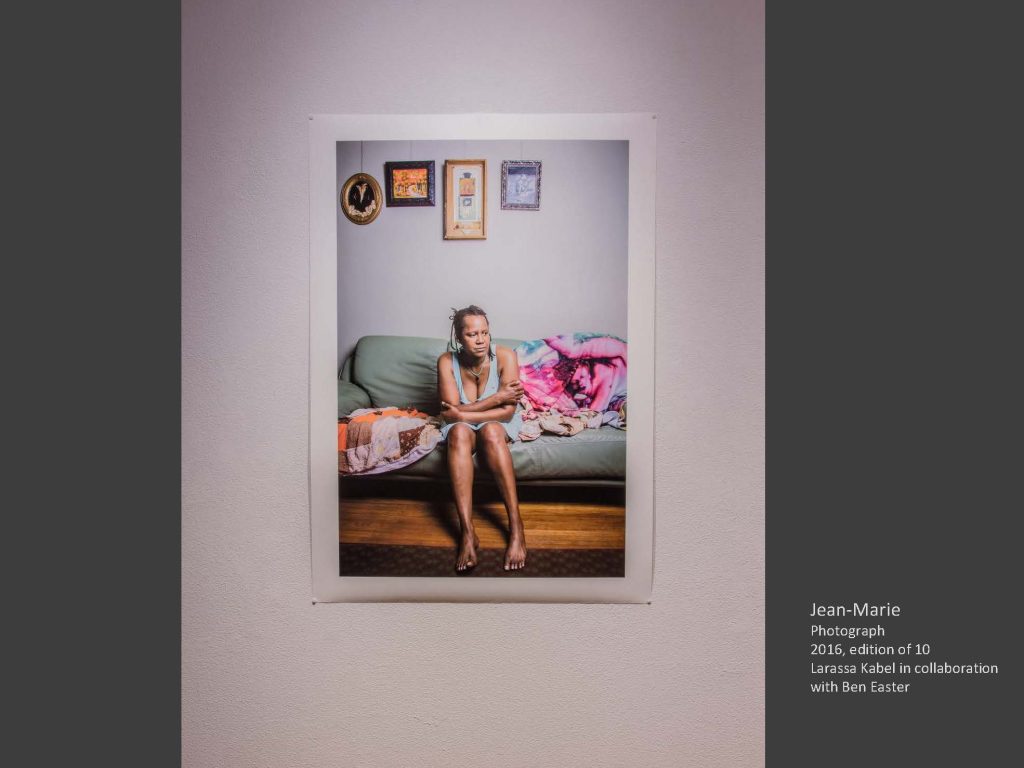

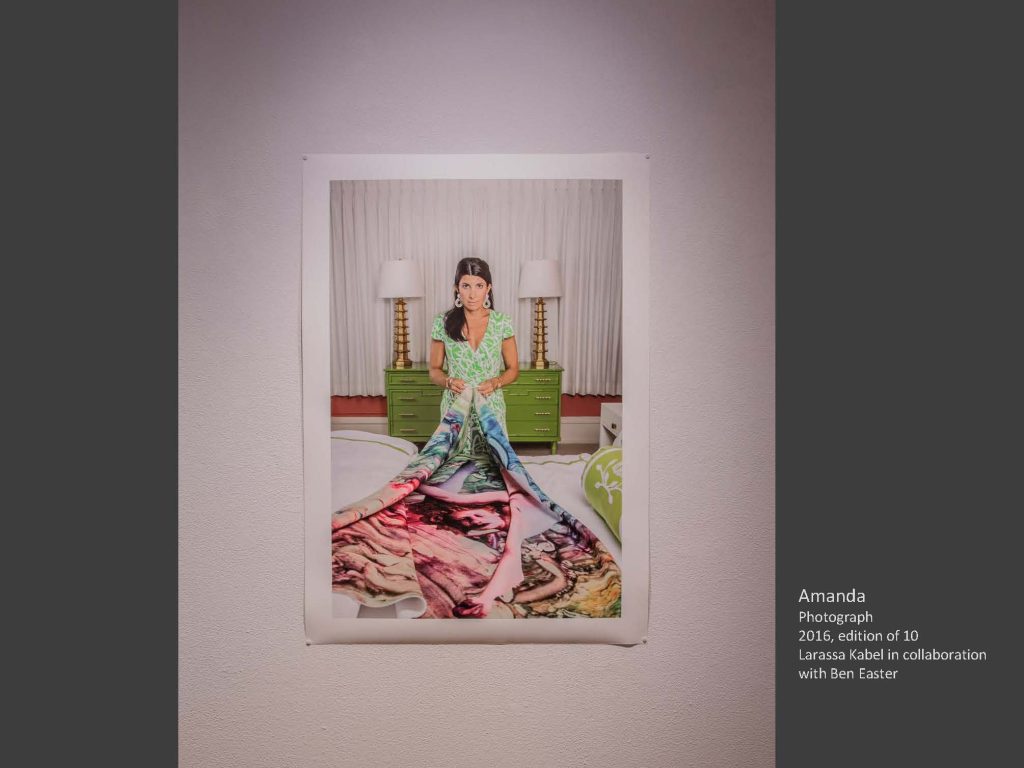

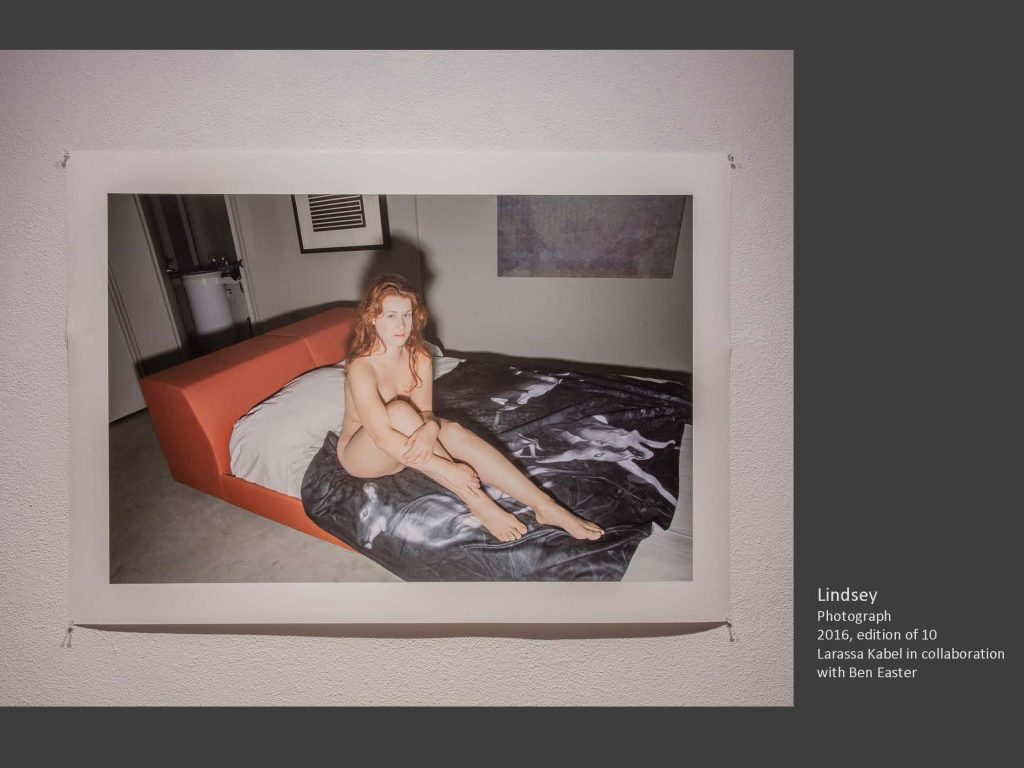

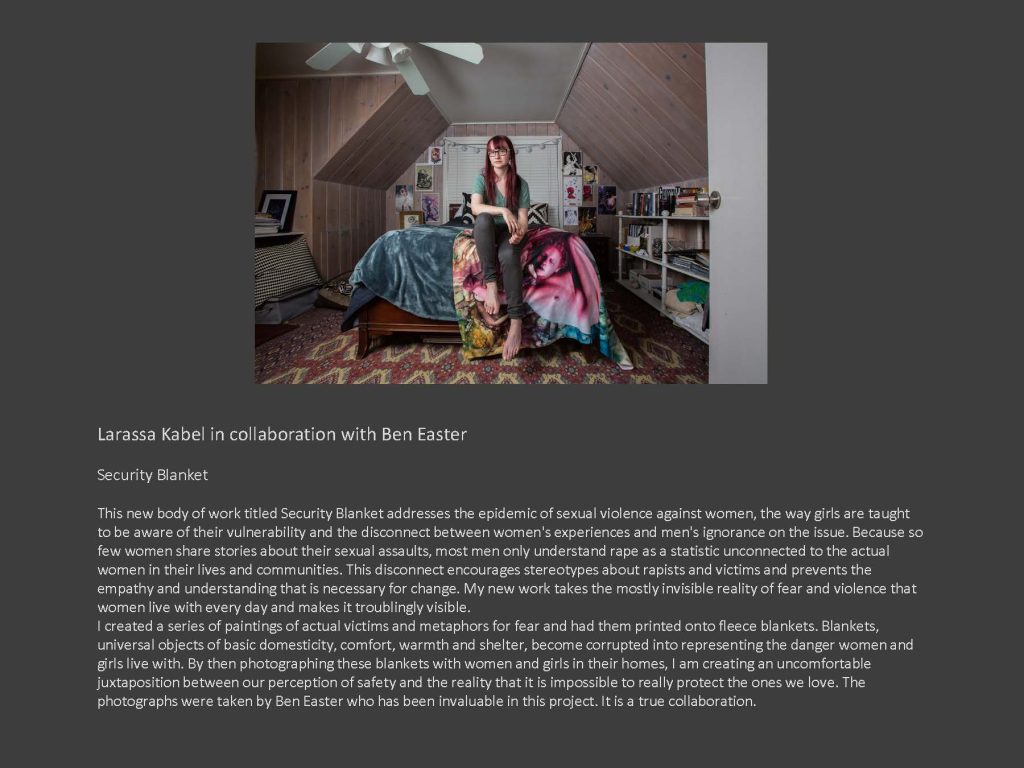

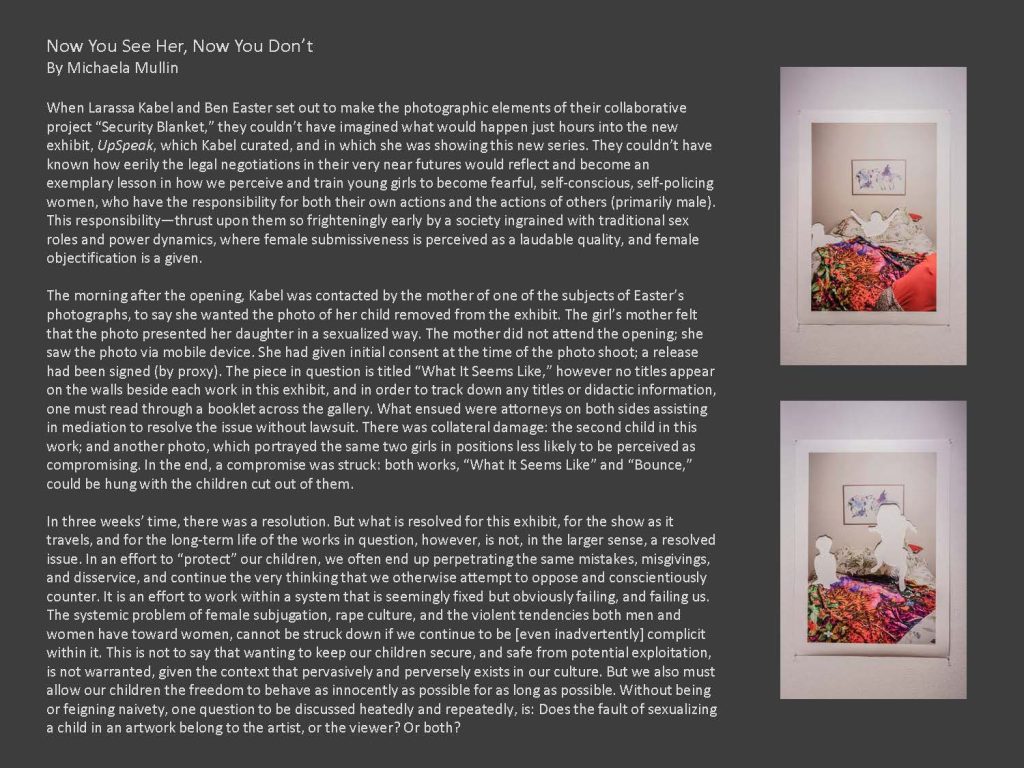

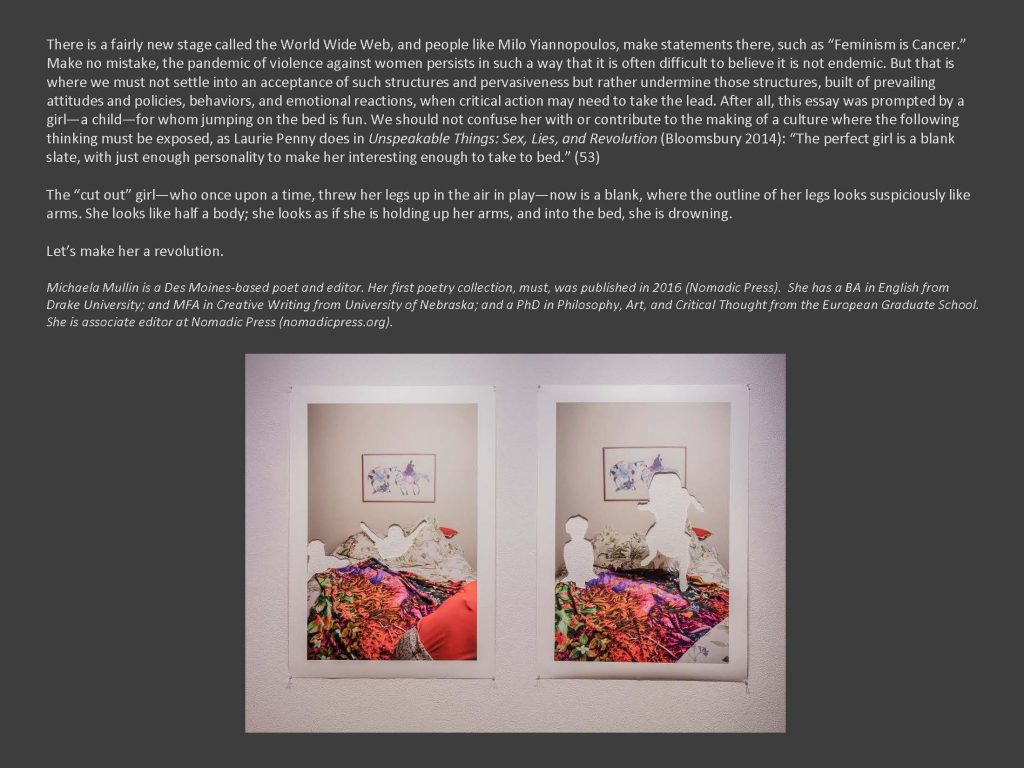

Kabel’s new series, “Security Blanket,” in collaboration with photographer Ben Easter, effuses the vivid colors of the rainbow. Confronting the “epidemic of sexual violence against women,” Kabel has created paintings of actual victims—some naked, appearing to float, some wrapped and placed in fields, semi-hidden amongst natural flora—and then had them printed onto fleece blankets. One blanket, “Scatter,” in black and white, captures fauna, doe, one of which looks out at the viewer with a blank, yet imploring, look of plea. The violence toward womanhood, motherhood, and girlhood, in these works gets transformed through the stage of victimhood and into survival, and each work within the larger body of work operates as a dispersive prism. For visibility is an issue that women must face and tackle everyday on different levels and to varying degrees depending on country, culture, career, economic status, and social standing. When it comes to the issue of rape or sexual assault, however, the already low visibility alarmingly plummets. The mise en scène of Easters’ photographs include females, old and young, black and white, of different social strata, as the set and dress of one subject indicates, in “Amanda,” herself dressed in the iconic Diane Von Furstenberg wrap dress. Each photograph prominently incorporates one of Kabel’s blankets, draped, being handled or used for cover, and the result is a kaleidoscopic story of being female (cis or trans) in the world. The protective nature of the blanket—which offers myriad forms of domestic comfort and warmth—in Kabel’s words, “gets corrupted into representing the danger women and girls live with.” A space, such as home, which should be a haven (as should any place we call home: neighborhood, city, country, world), is sadly yet another space in which oppression, repression, silence, and denial may continue to foster environments which grant exposure to assault.

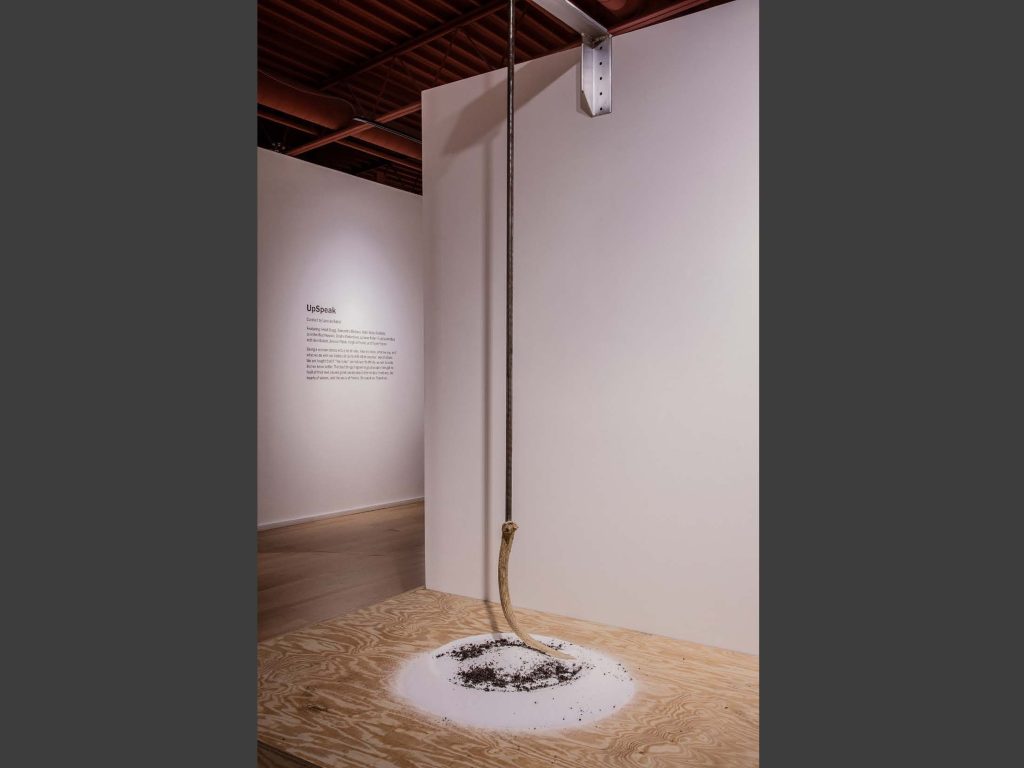

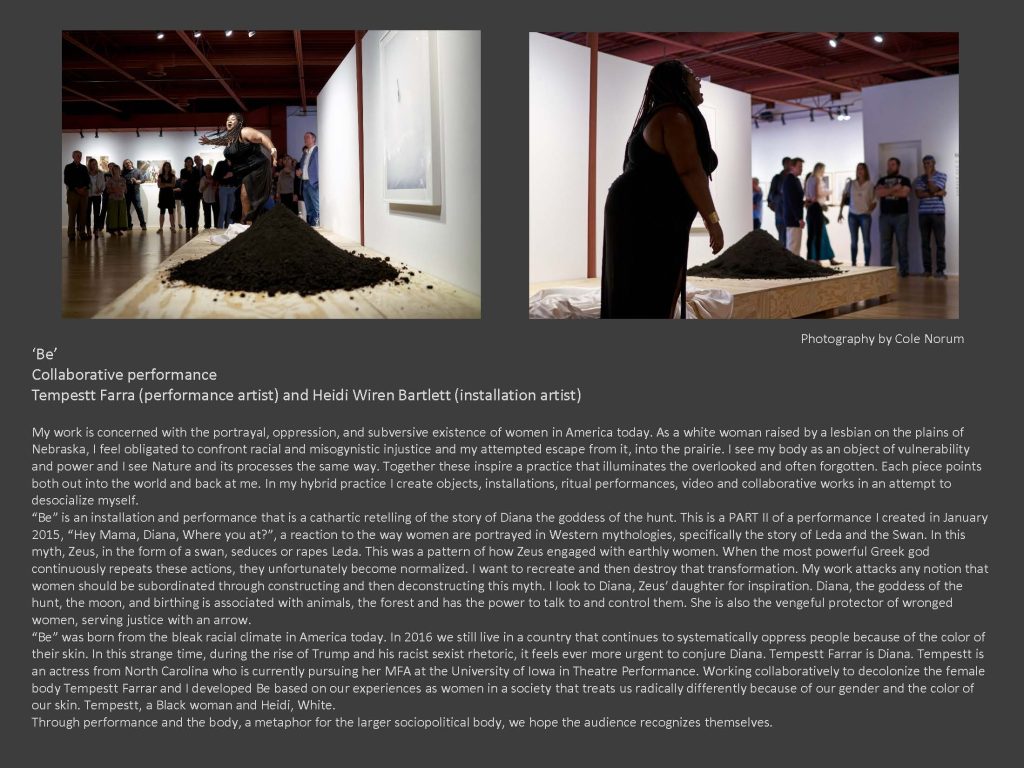

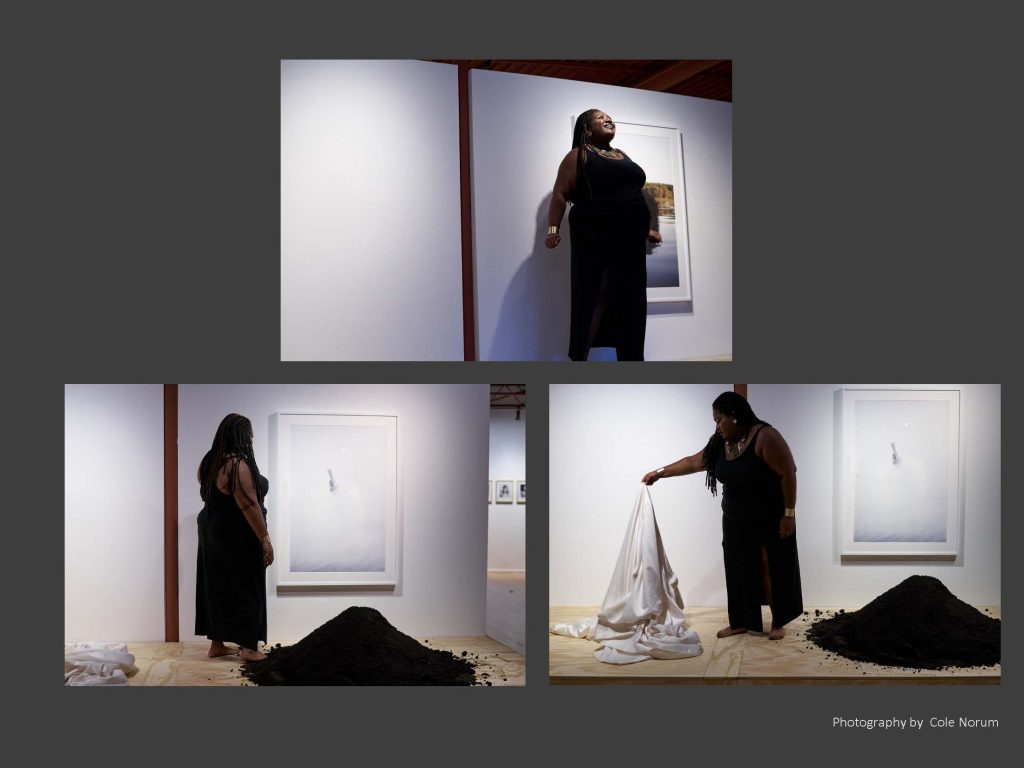

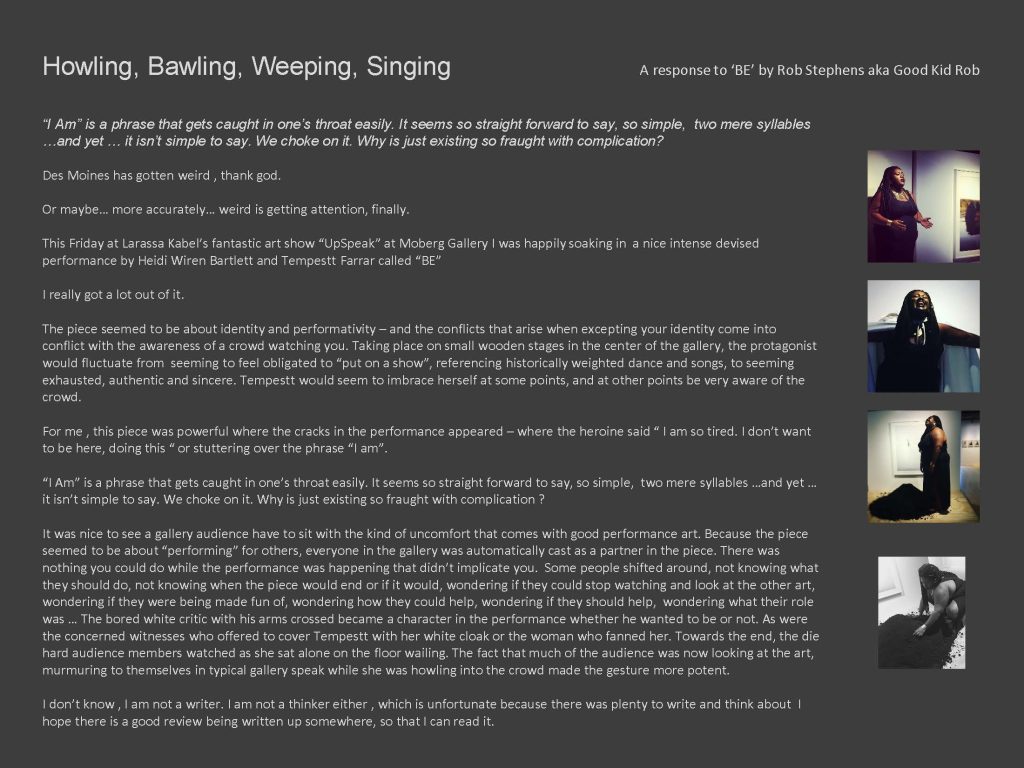

This potent exhibit puts forth particularities of these causal determinants, as well. Heidi Wiren Bartlett creates particular space with her intermedial works—space in which to move, space in which to observe, space in which to feel. Her installations and performances are works on the verge. The prepositional blank is what the audience must bring. Bring as gift. Bring as offering. Bring it on—and that is what the performer Tempestt Farrar does in Wiren Bartlett’s “Be,” a “cathartic retelling of the story of Diana, goddess of the hunt.” Farrar brings on a range of emissions—she emotes, she sings, she sounds, she touches, shakes and moves, and throws. She navigates the gallery goers, as well as the installation pieces, but she also interacts and extracts from both. No proscenium gets between performer and audience here, and that is discomfiting. It’s more than losing a fourth wall; it’s a true confrontation, and an allowance for the possibility of all persons in the space to be performative bodies, both in how they act, and how they react. Rob Stephens (aka Good Kid Rob), in a poignant post following his experience as audience member during “Be,” wrote the following: “The piece seemed to be about identity and performativity – and the conflicts that arise when excepting [sic] your identity come into conflict with the awareness of a crowd watching you.” Because to be watched can be empowering, but to be watched can also empty one of power, rob one of agency, and make of one an object. Wiren Bartlett and Farrar, White artist and Black performer, both women, spectacularly tackle and problematize the mythologizing and colonization of the female body.

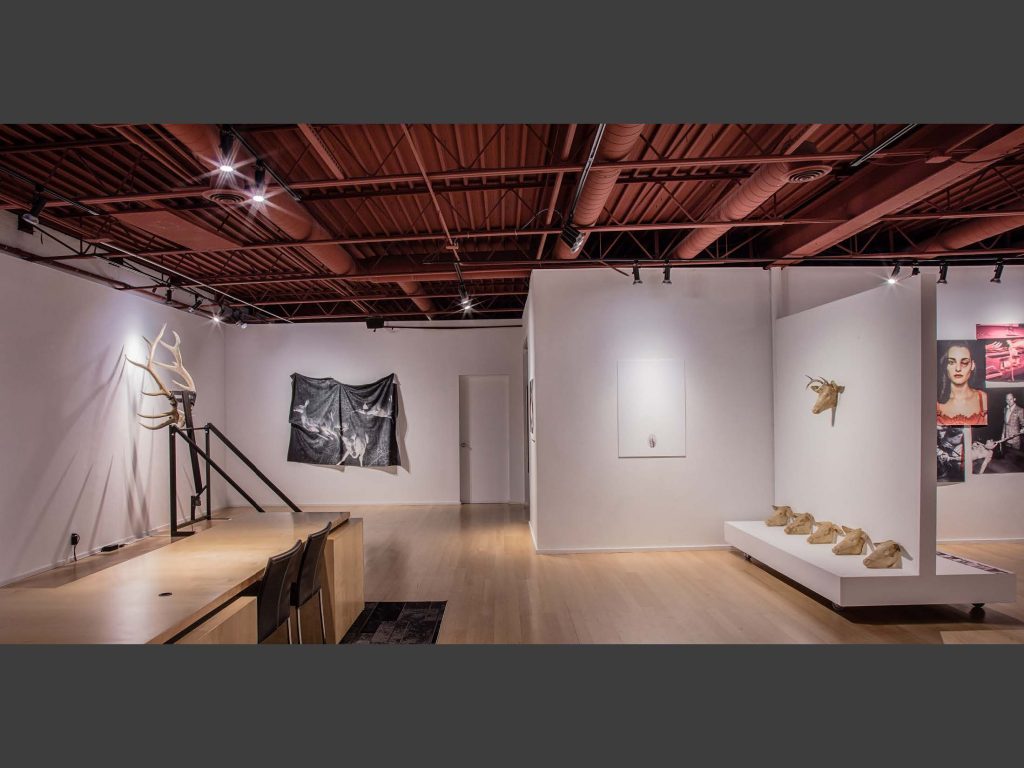

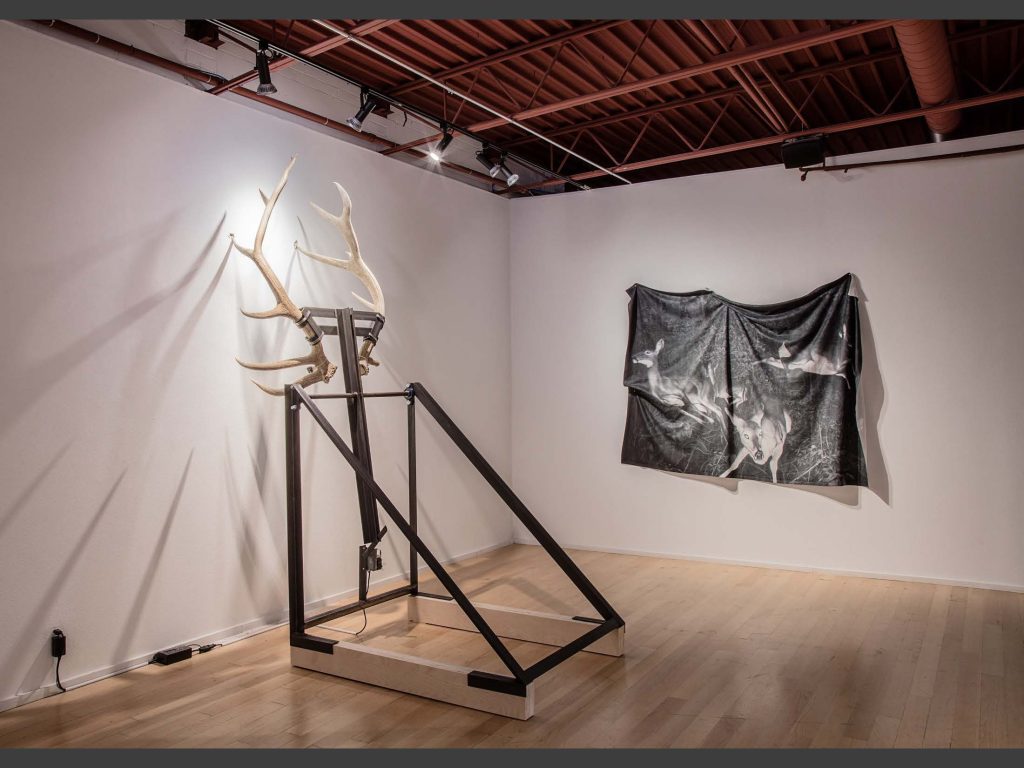

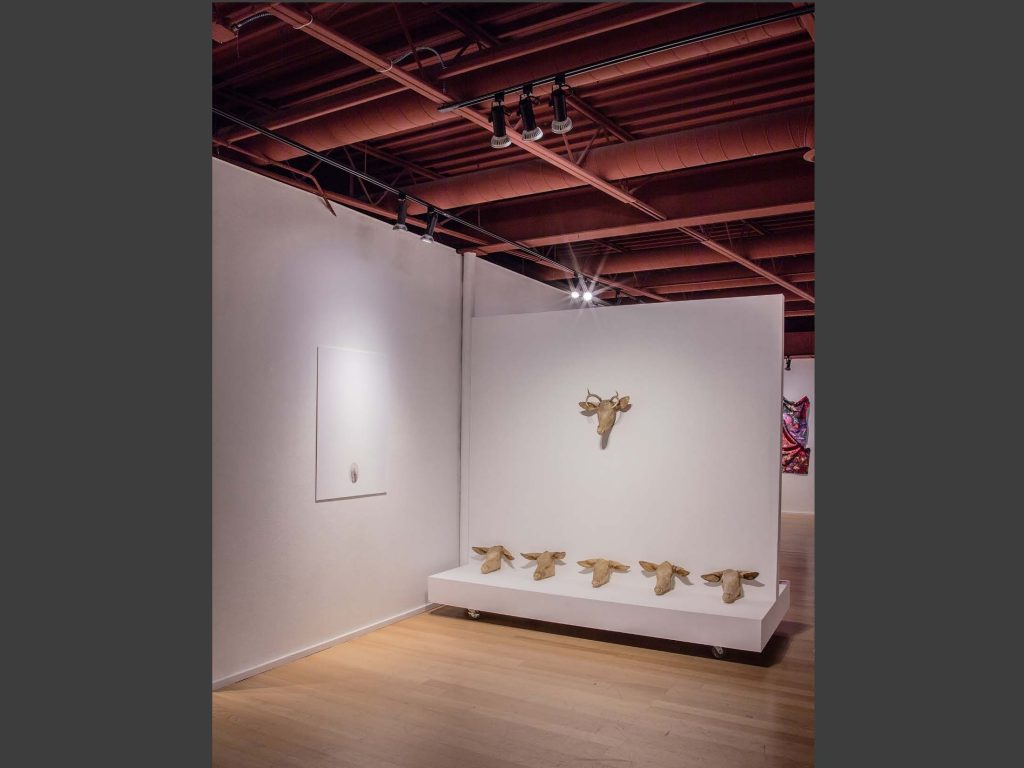

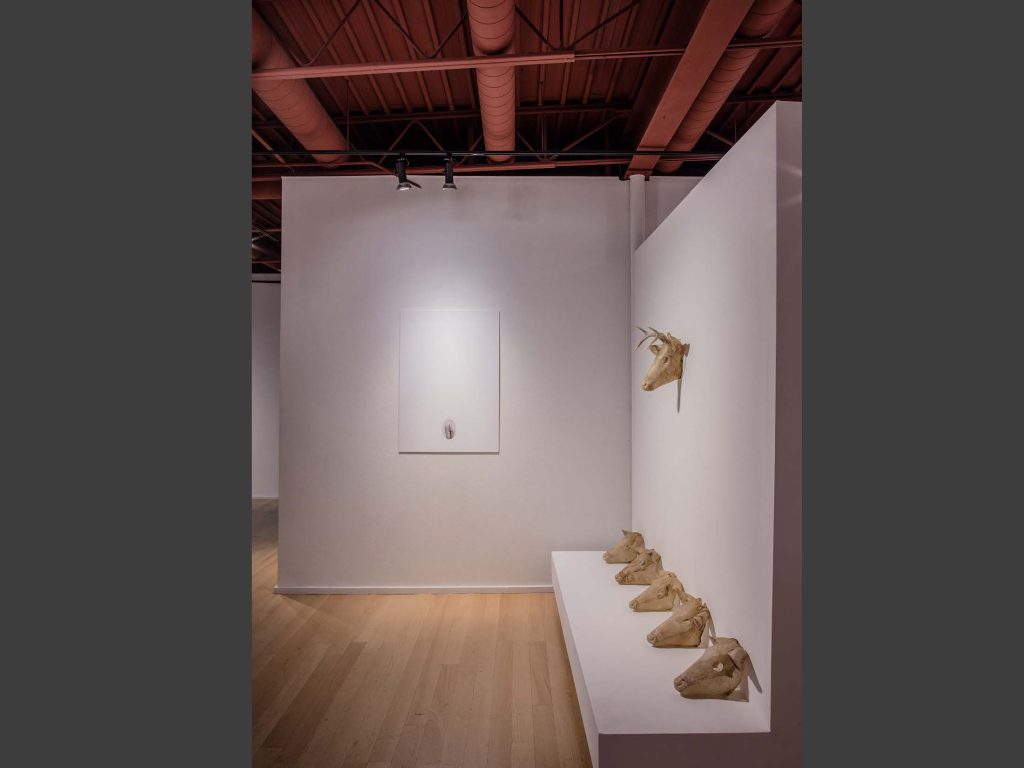

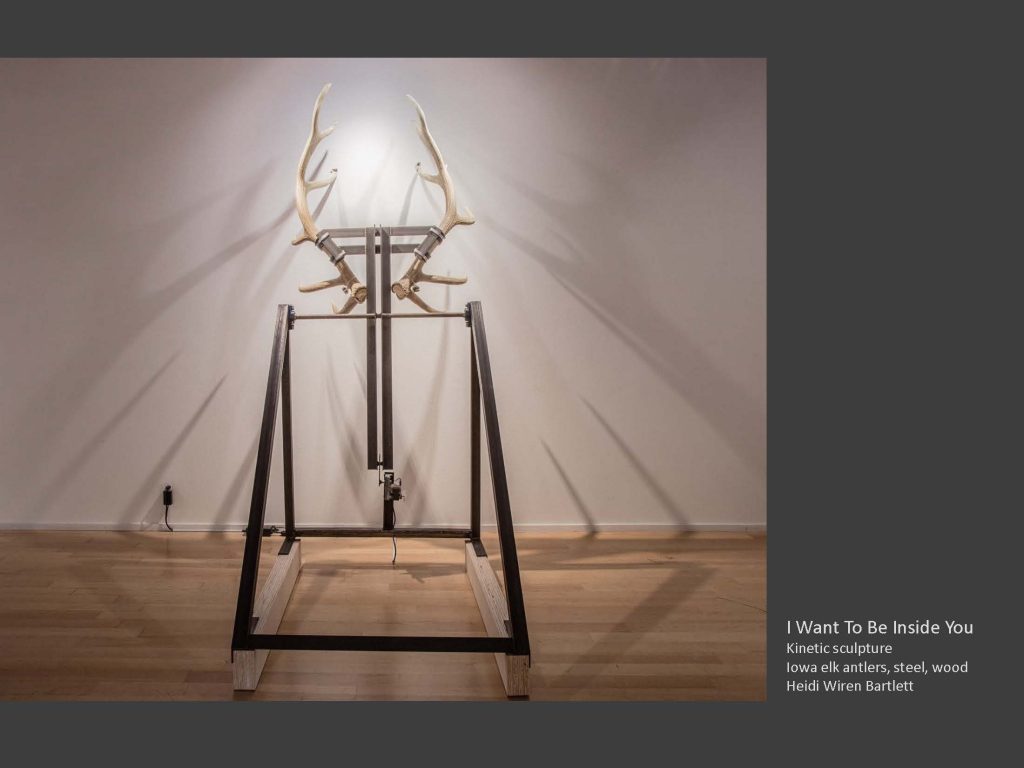

“I Want to Be Inside You,” Wiren Bartlett’s kinetic sculpture of antlers, steel, and wood, is on a timer, and intermittently moves its Iowa elk antlers, in bucking and locking maneuvers, into the gallery wall, creating holes in the drywall with its repetitive motion. This movement seems to mimic the way male deer or elk use their antlers as weaponry as a means to control their harems. The idea that such violent divisive tactics are taken as a means to maintain unity is not only seen in the non-human animal kingdom, of course. This large sculpture not only moves into blocked (walled) space, but the structure itself is reminiscent of equipment one might find in a gym. To be fit (for survival) has a whole new meaning, as does the utterance of this work’s title, I Want to Be Inside You. The polysemic nature of this title leads the viewer into territory where contradictory meaning is a layering one wishes, this time, could be monosemic (and loving).

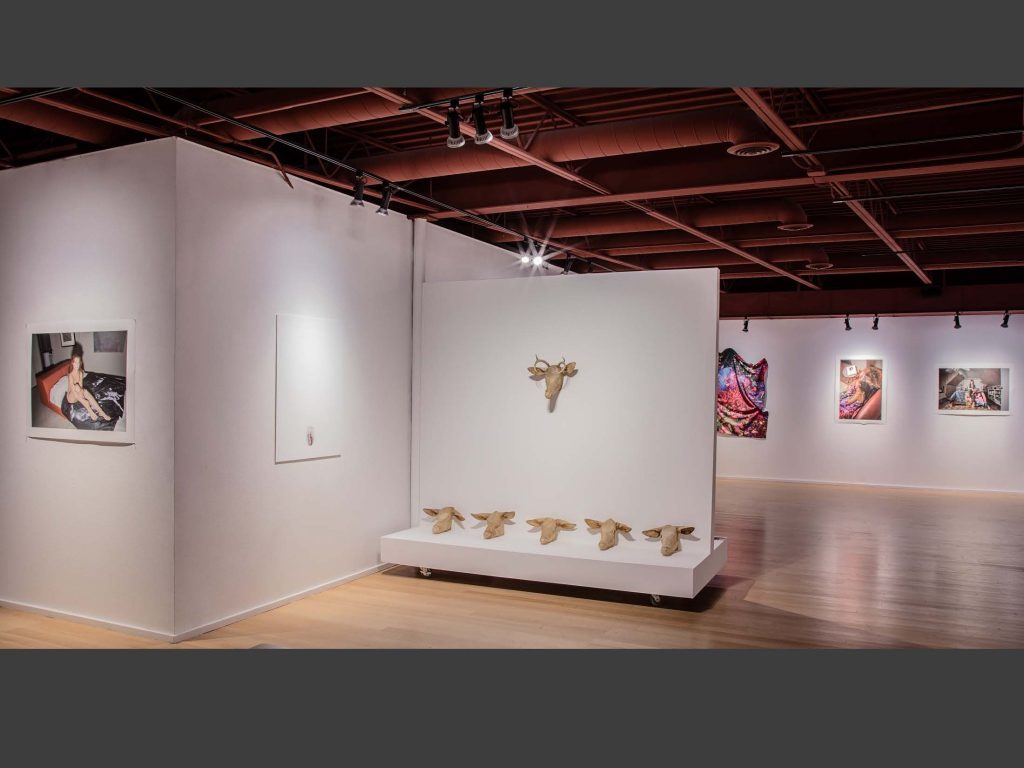

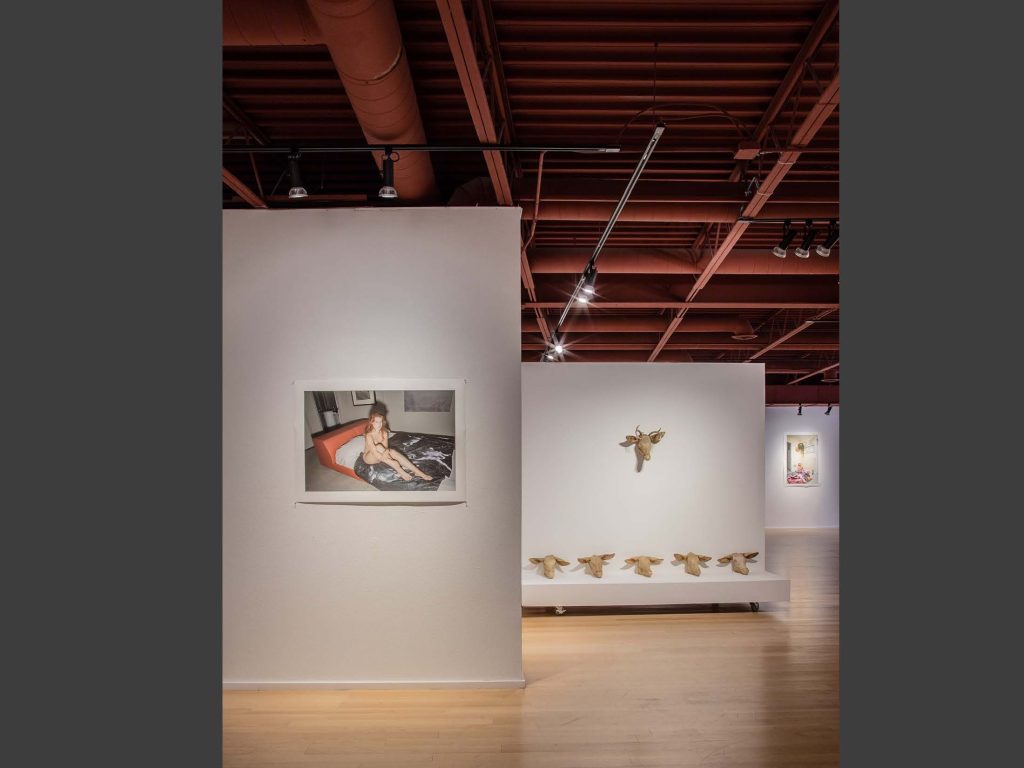

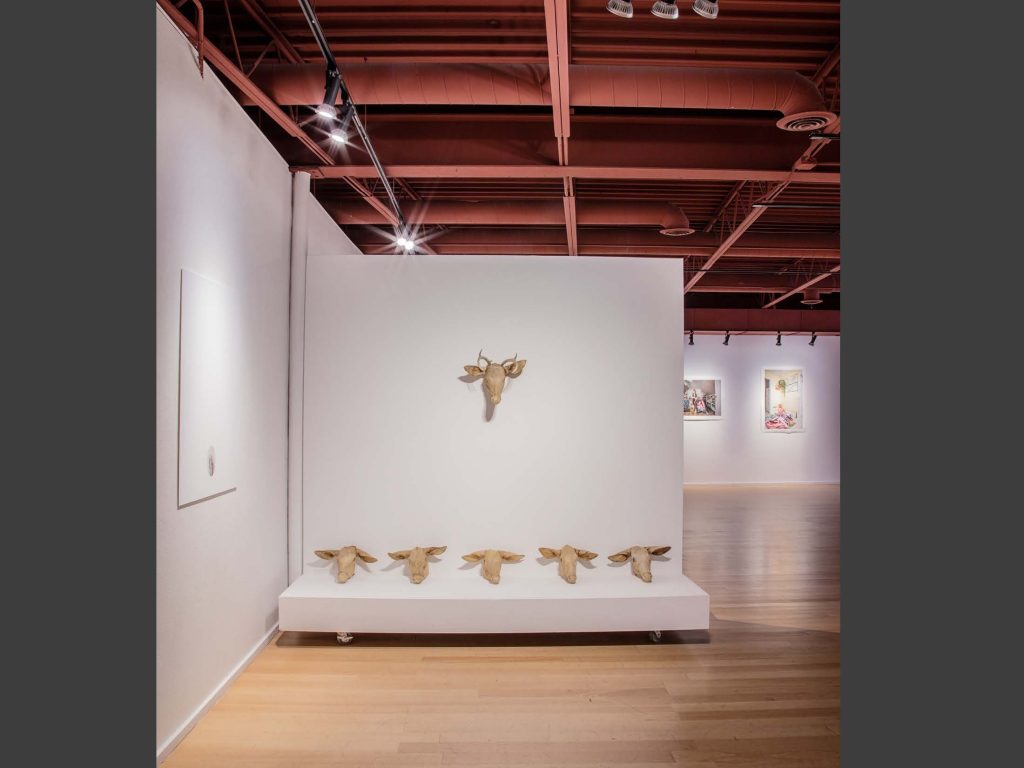

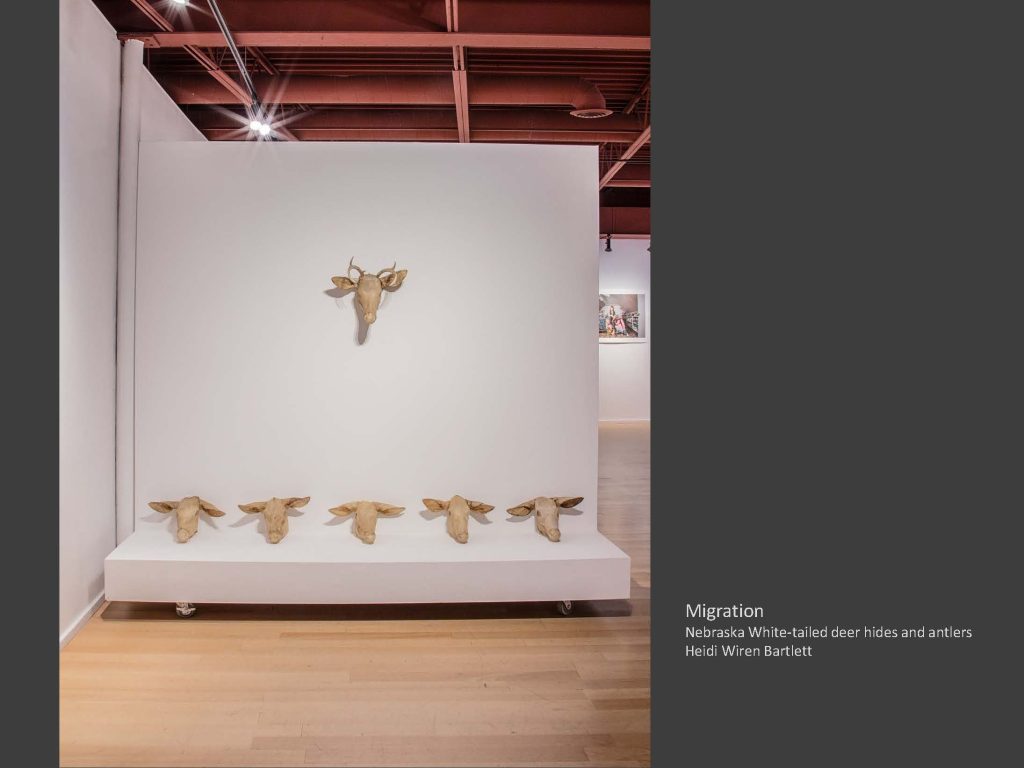

The deer hides in Wiren Bartlett’s installation “Migration” are lined up under a “header” antlered hide, arranged almost as if in a taxonomy of sameness (male leader, female harem?). A hollowing out of what once was flesh, muscle, organ. What once saw, thought, ate, licked. And are now remains. Hide, animal skin in the raw. For raw is an apt way to discuss Wiren Bartlett’s work, as it is concerned with using classification and ranking among animal groups to dispel what seems to be perceived as biological imperatives among the genus homo, human family.

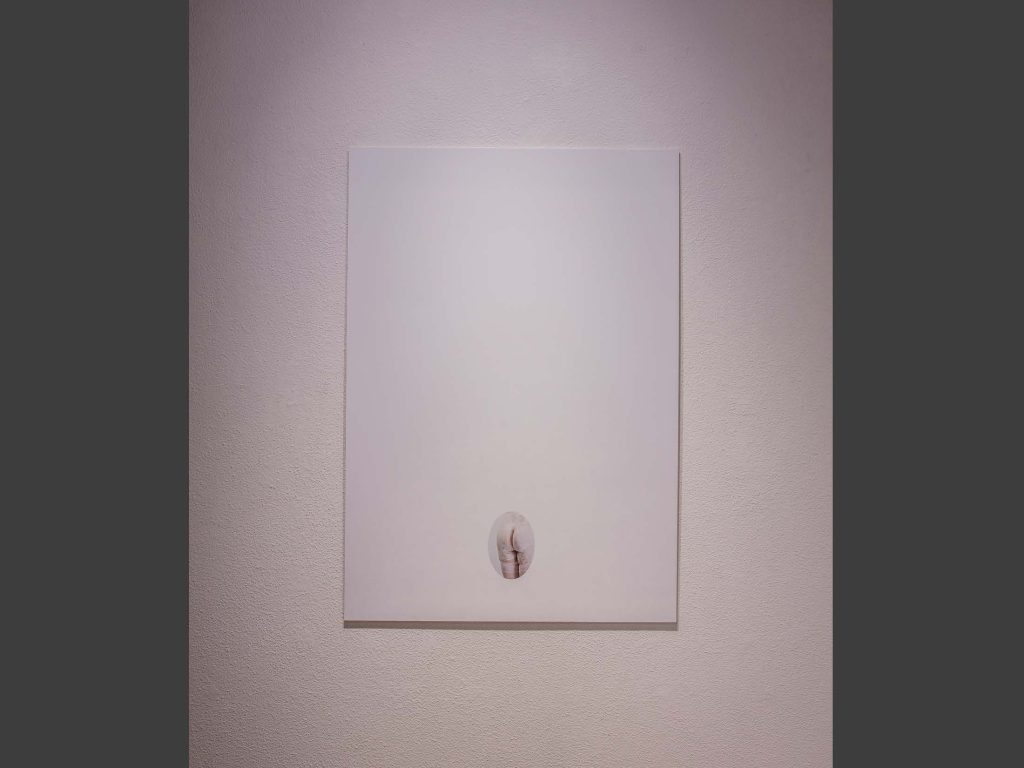

Wiren Bartlett’s documentation from previous performances is also moving in its seeming simplicity: white works that belie the flesh beneath the wash. These prints from “Noli me tangere” (trans. “Touch me not,” a collaboration with Kuldeep Singh), pull moments that highlight a performance with elements referencing Late Baroque/Rococo style, on the verge of Enlightenment, and are framed in a contemporary manner which harken back to the ovular-shaped frames of the Victorian period. Today, for future’s sake, we should harken to what these works say to us.

In the back hallway of the gallery, slightly hidden away, is Wiren Bartlett’s “Bow Down to the Queen of Noise.” This starkly beautiful diptych is, ironically, a very quiet work. Made of Nebraska pheasant wings and cut paper, these remnants of a dimorphic avian female, isolated from her nature and the males that out-colored her, can now be honored. All her singing, calling, and mating is revered now in its still form behind glass. The wings take up such little space in these frames, the white paper expanse behind them offers room to fly, metaphorically, now in their preserved art form.

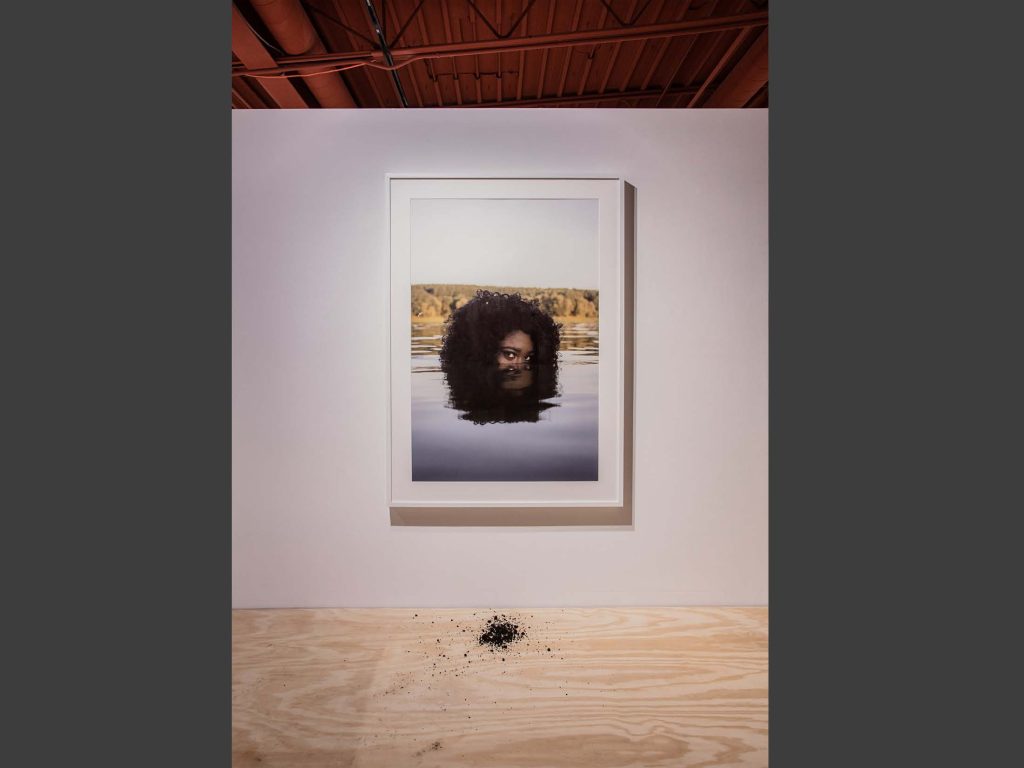

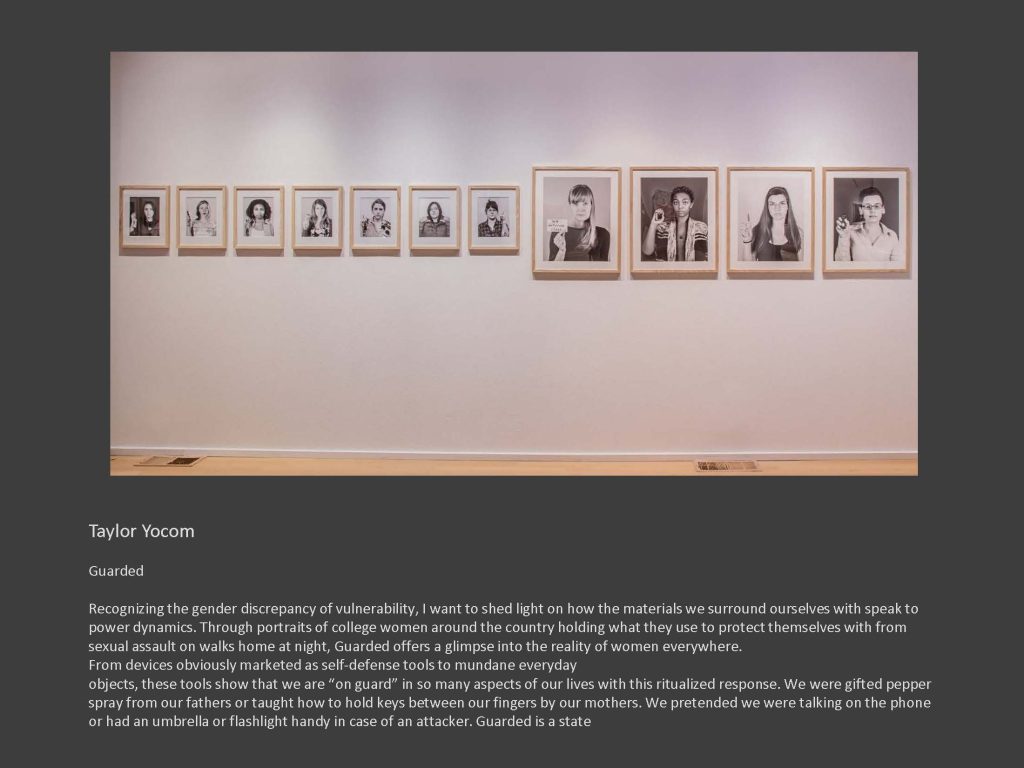

Taylor Yocom’s “Guarded” is a series of photographs which encompass a diversity of women; that these photographs are black and white helps to identify the universality of violence toward women. That all women are vulnerable to assault is an unfortunate truth; the choice to self-defend, or how to self-defend, however, varies by device and method. These portraits are close-ups, with no obvious punctum to lead the eye to the hands that carry each subject’s weapon of choice. For the women’s faces are, indeed, the foci of the works. Yocom says, “’Guarded’ is a statement on strength and vulnerability, giving a face to the articles and statistics.” These portraits capture straightforward, equanimous expressions, for the work is also a document, an archiving of the “materials we surround ourselves with [and how they] speak to power dynamics.” That all women, no matter height, weight, skin color, hair length, facial features, should protect themselves against a very real threat of violence is a disheartening fact. That the inequality that women in general face every day should find equality in this particular reality is heartbreaking. However, power may shift once a means of assertiveness and collective unveiling becomes commitment.

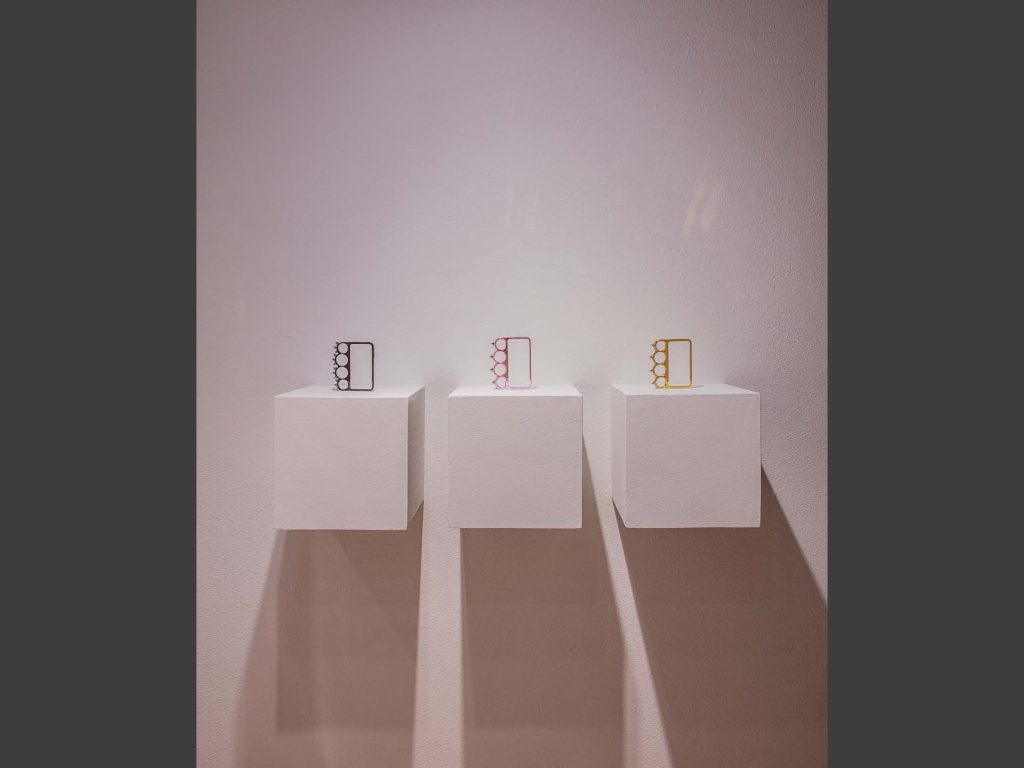

Jennifer Buchowski’s cell phone cases are more than decorative elements for your mobile—they don’t just embellish, they help the carrier “access” control. In a world of countless apps, the one application of the phone itself that wouldn’t necessarily come to mind is cell-phone-case-cum-weapon. Buchkowski’s “Spiked Brass Knuckles” turns bling to bang, while literally and figuratively giving women power in hand. It is an analog device for the digital age, and an unfortunate and timeless need in a vigilant age. But to empower and transform vulnerability (literally, wound-ability) into strength to protect one’s own body from harm becomes the force that must be reckoned [with].

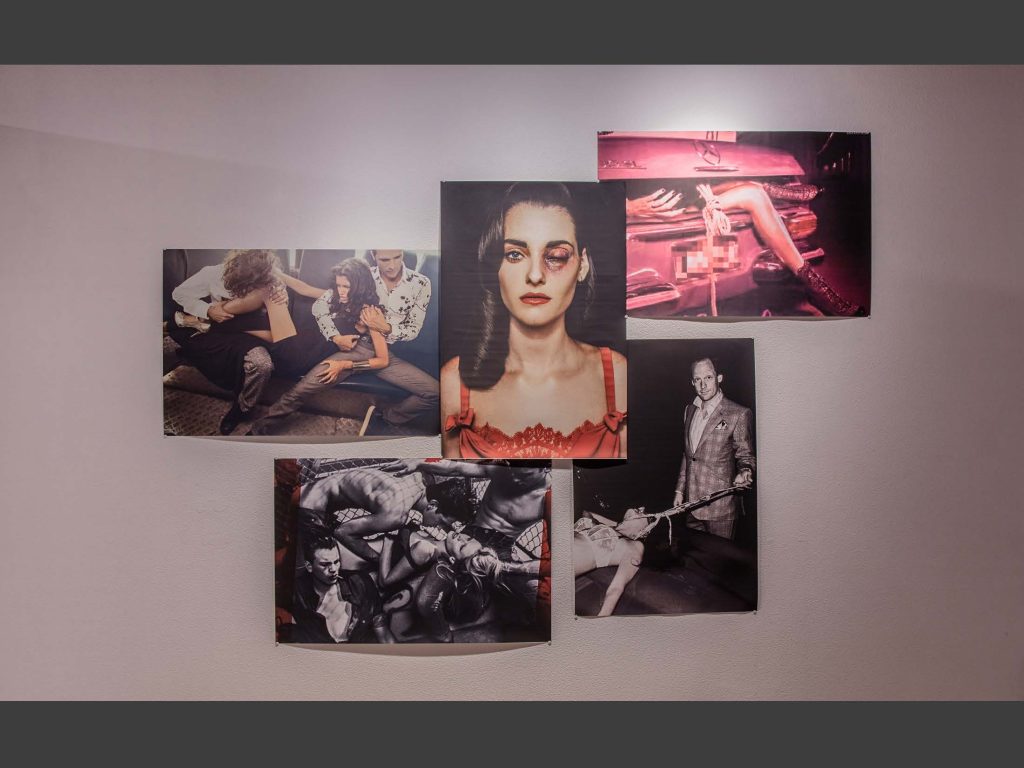

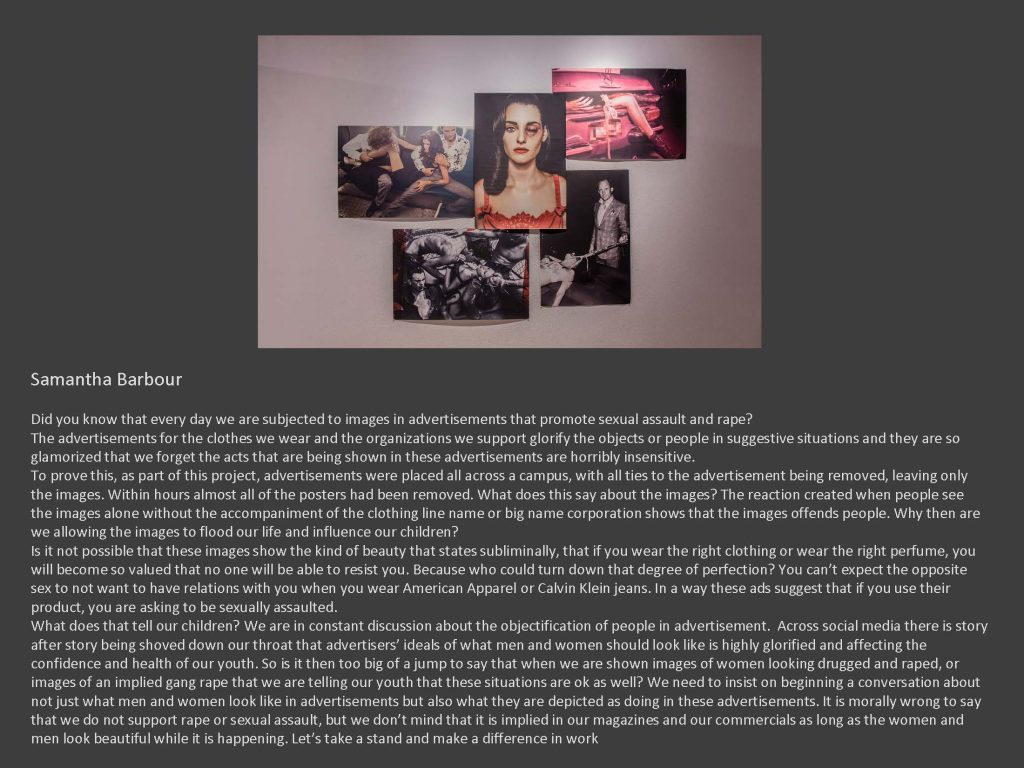

Samantha Barbour takes print advertisements from the fashion industry, and in removing all text and branding from the works, leaves the decontextualized images to speak for themselves. The horrifying results are narratives of abuse (a black eye), asphyxiation (a tie used for sexual purposes), disposal of female bodies (a leg protruding from the trunk of a Mercedes), or three (males) on one (female) in the consistently controversial Calvin Klein ads. In showing these ads in their naked aggression and perverse sense of beauty, Barbour asks that society “insist on beginning a conversation about not just what men and women look like in advertisements but also what they are depicted as doing […].”

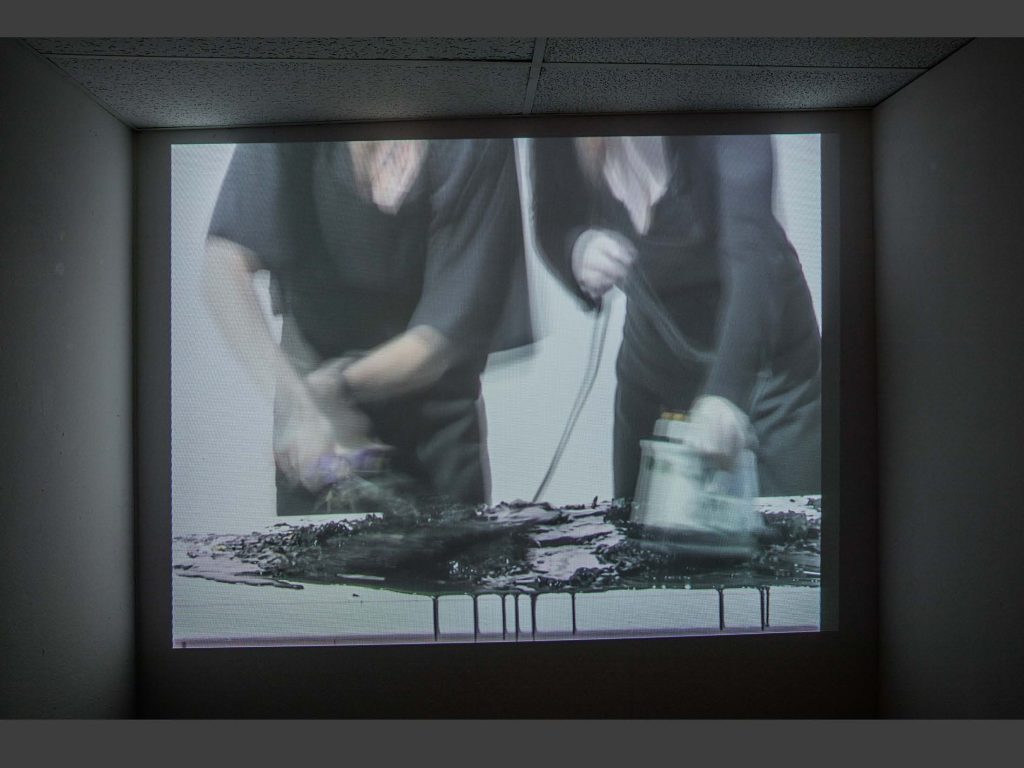

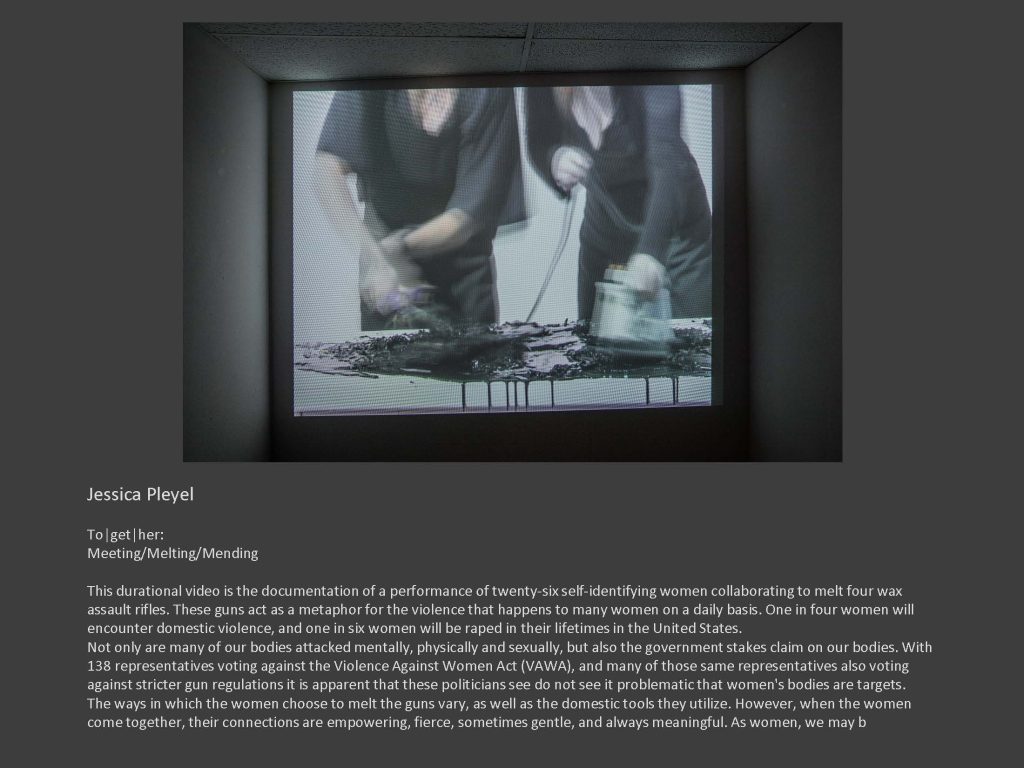

Doing is what the women in Jessica Pleyel’a video “To[get]her: Meeting/ Melting/ Mending” are occupied with—they are doing the work of metaphorically ridding the world of guns. They are blow drying and ironing out the means by which humans (mostly male) kill. The weak tropical response (as in the climate of the trope, not the equatorial area) heard too frequently to the argument against guns is: “Guns don’t kill, people kill.” Pleyel’s work is an eloquent repudiation of such sophistries, and is also a response to the staggering fact of the government’s dismissal of issues such as these: “With 138 representatives voting against the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), and many of those same representatives also voting against stricter gun regulations it is apparent that these politicians see [sic] do not see it problematic that women’s bodies are targets.” This performance documentation of the moving images of women melting “weapons” is a much more useful and smart way of bringing heat.

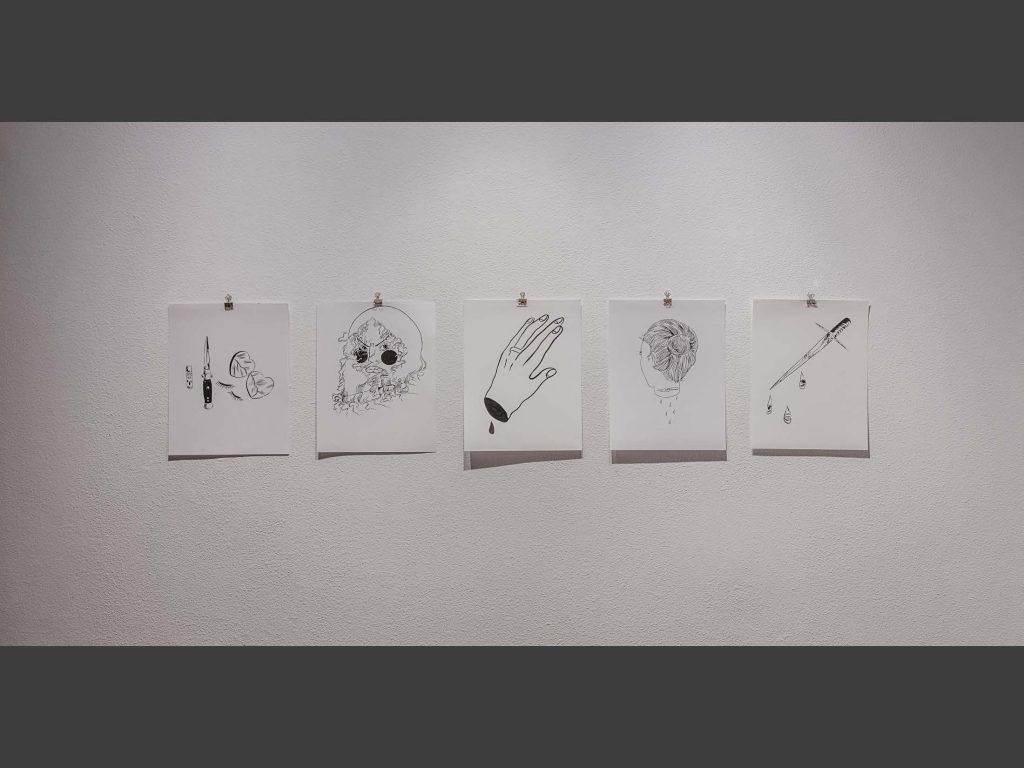

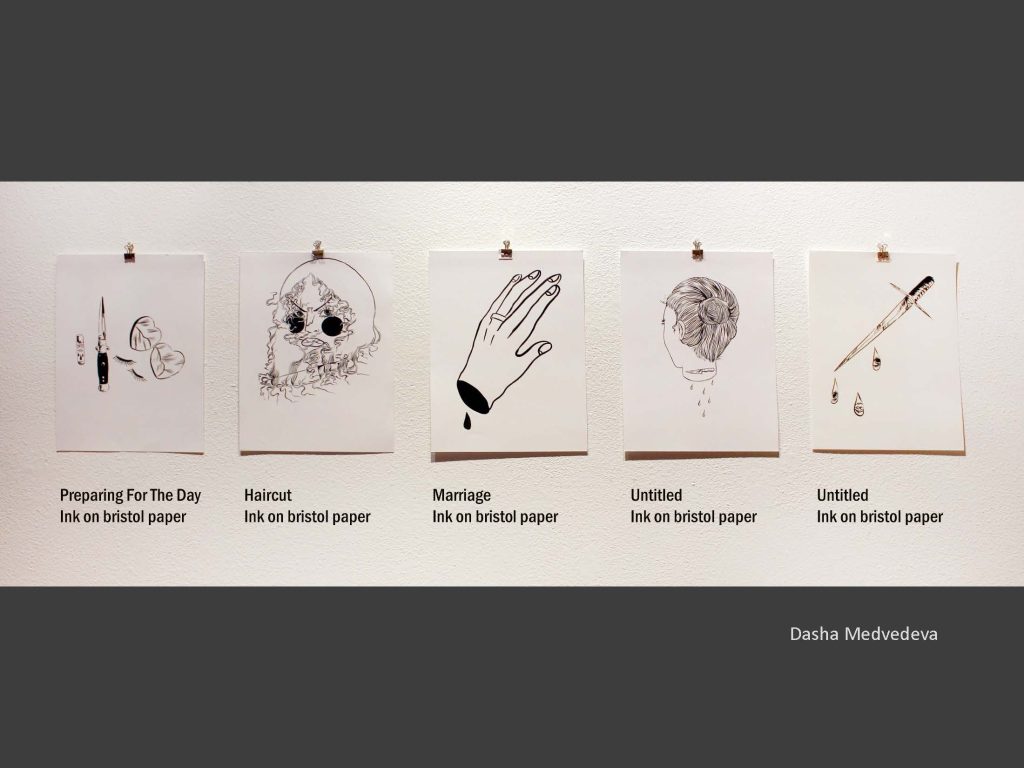

Dasha Medvedeva’s five ink works on Bristol paper are intended to cause discomfort. Medvedeva wants to shock as a means of pulling viewers out of the slumber that less-horror aesthetics may induce. The body parts that are the subjects of “Marriage” and “Untitled,” initiate discourse about what it could mean to give one’s hand in marriage or to be a body severed from the thinking head—to give and not to receive; to be faceless, untitled (except in the form of a familial, patriarchal or spousal naming). The dark stark lines of Medvedeva’s work are influenced by graphic novels. Her history with the comic book has an important bearing on her style, and her compositional approach is effective as visual storytelling without textual components. In “Preparing for the Day,” the paraphernalia associated with female getting ready-ness is drawn without a surface space, five objects floating on the page: lipstick, a pocketknife, two false eyelashes, and Lolita sunglasses. The insertion of a dangerous weapon among such seemingly banal items—but if painted lips, and longer, lusher eyelashes and provocative shades (with possible reference to statutory rape) are societally perceived as “invitations” to assault, then the knife’s presence counters that invitation with a potential declination. As long as the female body and beauty is presented for male consumption and gaze, or any outside gaze, the objectification of women will necessitate that the knife be included in this grouping.

UpSpeak is an exhibit about voice and sight, it’s about visibility and subjectification (for individuals comprise and achieve community)—it is about shifting, even reversing the gaze. Herein, women and victims/survivors—the vulnerable and purportedly weaker sex—look back at the audience in the hope the audience will continue to look at themselves, as well as at dangerous, if not criminal, societal permissions. This exhibit is an attempt at a more circumspect viewing of a subject, in order to create a clearing, if not clearer vision, which can then be translated into intellection and actionable realizations. A conversation can be protracted from this exhibit, which dispels the ignorant and angry opinion that those who want to face the truth of how women are violated have an axe to grind. It brings light to what is really happening in these conversations: lens grinding for better visual acuity.

Exhibit Images

Exhibit Images